Biotech development is reshaping New Haven here’s why

From major building projects to new companies to educational pipelines, biotech is reshaping New Haven

Construction is nearing completion on the 101 College Street laboratory tower. The parcel at 101 College Street was reclaimed as part of the Downtown Crossing Project, a partnership between city, state, and private actors to reconnect downtown New Haven to the Yale Medical School campus using a biotech industry cluster.

The third floor of the Pierce Lab, a philanthropic research organization in New Haven, underwent a major change during the pandemic. The old lab space where volunteers pushed their bodies to the limits for Project Daedalus, a human powered aircraft experiment, were gutted and renovated into a biotech incubator, New Haven Innovation Labs.

The result is a glimpse of a new economic engine transforming New Haven as science labs and fledgling biotech companies grow and expand. Already, two companies that started at the innovation labs have moved on to larger spaces in Connecticut.

“In the year they’ve been here the companies have raised over $20 million and added 38 employees,” said Kim Kelly, vice president at Biotech, a nonprofit that supports bioscience growth that is working with New Haven Innovation Labs. “That’s a good statistic.”

Twenty years ago, there was barely any private lab space in New Haven proper. West Haven was still home to the Bayer campus. The startup scene wasn’t really present, and the site of the new lab tower was a highway spur. Now there are more than two million square feet of lab space in New Haven. Yale alone spins off roughly ten startups every year from its massive patent portfolio. Biotech is booming.

According to analysis by AdvanceCT, a nonprofit economic development group, Connecticut ranks second in academic bioscience investment and third in bioscience venture capital funding. The state has the fourth highest number of bioscience patents. New Haven anchors a substantial portion of the state’s biotech real estate market.

“All of this creates momentum,” said John Bourdeaux head of business development for Advance CT. “The investments that have been made in the past and will continue to be made in New Haven will have a magnifying effect statewide. That will spill over into adjacent towns and throughout the state as well.”

New Haven also happens to be in the middle of two major biotech hubs, Boston and New York, with lab space costs that are roughly half to roughly a third of the cost. Cost of living is also cheaper here, relative to other biotech hubs.

“There’s this misperception that if someone moves to Connecticut for a role (in biotech) and the company goes bust they’re not going to find another opportunity. But there’s much more happening here than people understand” said Jodie Gillion, CEO of BioCT, which worked to help develop the innovation labs. “There’s this budding ecosystem.”

A city that makes sense

The parcel at 101 College Street was reclaimed as part of the Downtown Crossing Project, a partnership between city, state, and private actors to reconnect downtown New Haven to the Yale Medical School campus using a biotech industry cluster. Downtown Crossing used to be the Route 34 expressway, a highway spur that divided this area in half.

As Route 34 came down, replaced by frontage roads, shining laboratory towers went up. 100 College street is home to a 14 story tower divided between Alexion and Yale. 101 College Street will house local companies Arvinas, Alexion Pharmaceuticals and 58,000 square feet of incubator space.

“Boston is amazing but it’s super expensive,” said Dr. Ranjit Bindra, a professor of radiation oncology at Yale and serial biotech entrepreneur. He rattled off the transit options, the music and restaurant scene and the travelling theater companies that come through. “You want a place with a good cost of living and good access to Boston and New York … schools living by the shoreline. Mix that all together and you can see why this makes sense.”

Meanwhile at New Haven Innovation Labs, researchers working out of the medical campus can rush across the road to check on their startups.

“There’s been a big push in the city of New Haven and state of Connecticut to have people stay here and do science here instead of rolling out of Yale and leaving,” said Chris Vandola, operations director for the lab space. “We wanted to get involved with that.”

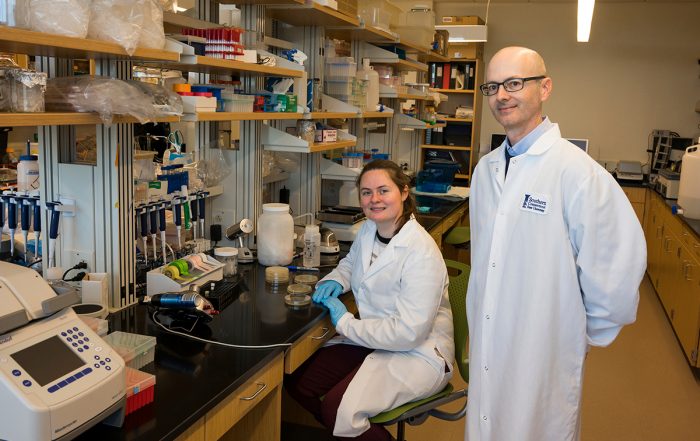

BioCT, a partner with the New Haven Innovation Lab, is a professional organization that represents the Connecticut biotech industry. They also provide discounts, networking, and a pair of incubators, one in New Haven and one on the Pfizer campus in Groton to members.

“We want it to be a turnkey so they can move in and just start,” said Kim Kelly vice president of BioCT’s incubators. She ran through a laundry list of expenses including specialty equipment and insurance. The renovation at New Haven Innovation Labs took about $1.5 million to get the labs up to modern spec. They range in size from small, shared lab benches to 1,000 square foot private spaces.

Kelly said that BioCT’s incubators were designed to be turn-key. “It allows them to stretch their capital. If they had to build their own space the VCs are not interested in that for an early-stage company.”

Partnership with Yale

“There was a company called Curagen, the granddaddy of all the life sciences companies,” said Robert H. Motley senior director of Cushman and Wakefield, a commercial real estate company. “They struck a billion dollar licensing deal … that was the wake up call that life sciences was going to be a big deal in Connecticut.”

At around same time, Yale got in touch with developer Carter Winstanley, who had been working in the Cambridge area developing lab space.

“They expressed an interest in having a partner in town who could create private sector life science space in close proximity to the university,” said Winstanley. “These companies are formed off science coming out of the university, so there’s a highly collaborative environment in place.”

The first building Winstanley identified was an old telecom building at 300 George Street. He converted this half-a-million square foot building into 5,000 square foot incubator lab spaces. As those spaces filled up Winstanley and Yale looked for more candidates.

New Haven had a significant stock of buildings that were compatible with the heavy machinery required to for a lab setup.

“In the early 2000 everyone who owned a commercial building was throwing their hat in the ring saying I can do life science,” said Motley. “But the reality is that 95-98 percent of these owners have no idea what’s involved.”

Unlike a traditional tech company, where you can start out with some computers and desks in a room, biotech has demanding physical needs. Motley ran through a list. Labs need a lot of power, advanced HVAC, gas, suction and floors that can bare heavy equipment. Lots of office buildings just can’t accommodate these things. New Haven could.

What is now Science Park was the Winchester Firearms manufacturing campus. Those buildings, Motley explained, were built with strong, vibration-resistant floors, and could accommodate massive HVAC systems. They also happened to be cheap to buy.

“With an old factory building you could take all that ductwork and run it through an old freight elevator shaft,” said Motely. “Or you’d take these massive exhaust systems and bolt them to the side of the building, signaling to the neighborhood Hey I’m a Life Science Building.”

These spaces paved the way for biotech startups to stay in New Haven. While many of the initial class of those startups have gone under, or were bought out, others have put down roots. In the case of Alexion, it was both purchased by Astra Zeneca and left intact as a research department.

“These companies that spun out of Yale really started to stoke the fire of biotech development,” said Dr. Bindra. “Once you get those big anchors it becomes easier and easier for other companies spinning out of Yale to stay in New Haven.”

This created more demand for lab space. Winstanley recounted a conversation with a startup tenant of his at 300 George. The tenant pointed across the Route 34 Expressway to the medical school.

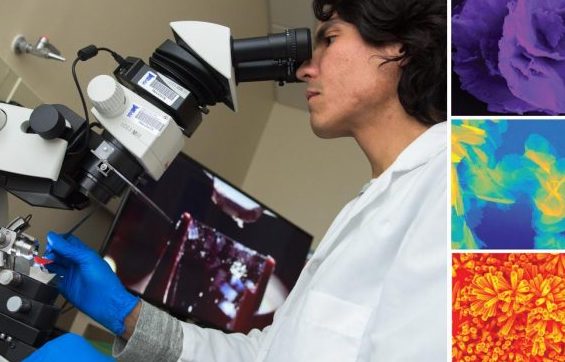

“He looked at me and said, our success depends on the scientists in that building coming over here for lunch, looking through our microscope and letting us know if we’re headed in the right direction,” recalled Winstanley. “If you put me down on Long Warf that’s never going to happen.”

More than just jobs

New Haven escaped the biotech crunch that hit the larger hubs in Boston and San Francisco this year. Growth here has been steady. But everyone agrees that there remain some real challenges to keep the momentum going.

Housing, for one, could hold back the biotech wave now boosting New Haven.

While New Haven leads the state in terms of new apartment construction, it’s still not enough. According to reporting in the New Haven Independent last year, there was a 8,300 unit shortfall for low-income renters and a 3,200 unit shortfall for higher income renters. Suburbs have not kept up with the pace of New Haven’s development. Winstanley said that the amount of residential development wasn’t enough.

“There’s a real need for cost-effective residential options,” said Winstanley. “I don’t think we have enough out there and there’s got to be affordable opportunities as well.”

Winstanley was adamant that the growth of biotech wasn’t just about bringing jobs to the city.

“I want kids walking out of this building feeling like they are entitled to the jobs here, that they are comfortable with these jobs,” said Winstanley. “I want them to graduate and come back and work in the building that their mom or dad built.”

He pointed at the connections 101 College Street would have to the New Haven public school system, a scholarship program, and the Biopath program at Gateway Community College and Southern Connecticut State University.

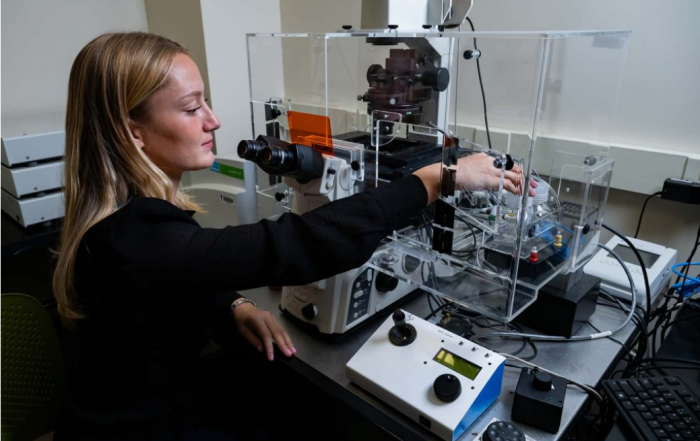

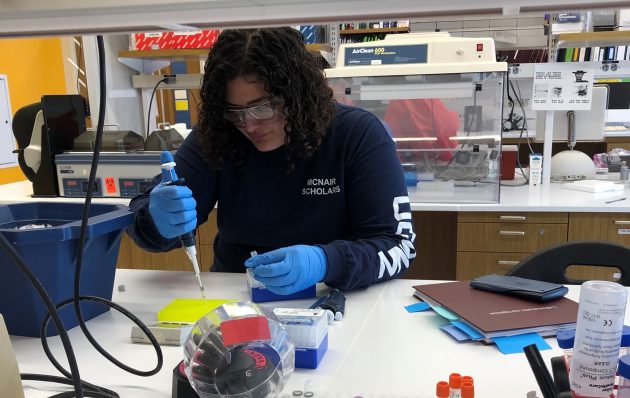

“We see internship postings that say students need two years of experience. Students ask, how am I supposed to do that,” said Peter Dimoulas grant program administrator for BioPath. “That’s where we come in.”

BioPath has in the past year placed 38 students in jobs and internships. They also provide financial support to students trying to enter biotech through scholarships. They’ve been working with the New Haven public school system to get local kids excited about biotech.

“The students go into those labs, behind the proverbial steel and glass panes to see what’s going on,” said Dimoulas. “And they imagine, hey, I could do that.”